The experiment addresses questions like "Does color inhere in the world, or in the eye?" It is a re-creation of Edwin Land's retinex theory experiment.

What It Shows

Color is not actually a property of light or of objects that reflect light; it is a sensation that arises in the brain. Unlike a spectro-photometer, which cannot categorize the color of objects, the eye has evolved to see the world in unchanging colors, regardless of unpredicatable illumination. Edwin Land dramatically demonstrated the phenomenon with his "Color Mondrian" experiment and posited a retina/cortex system (retinex) explanation.1 The present demonstration is a simplified re-creation of his experiment.

How It Works

Three projectors2 with band-pass color filters3 are set up to illuminate a 2'×3' poster with red, green, and blue light. Three independent brightness controls4 adjust the light intensities so that illumination can be mixed in any ratio. The poster is a collage of different colors of paper.5

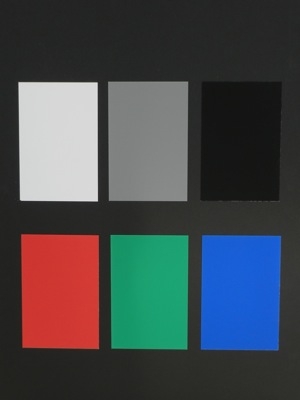

Before performing the experiment on the collage, it might be instructive to first define what it means when an object appears "white" in terms of what wavelengths of light are reflected. To that end, one would start with a different poster that has white, gray, and black paper on it (in addition to red, green, and blue). A telescopic photometer6 is used to measure the amount of light reflected off the piece of white paper.

Generally speaking, when we perceive an object as being white, we reason that the object must be reflecting all parts of the visible spectrum with equal intensities. Since red, green, and blue provide a broad sampling of the visible spectrum, one would think that if the object reflects equal intensities of red, green, and blue light, it will appear white. To show that that is indeed the case, illuminate the poster with just blue light. With the photometer, measure and note the intensity of blue light reflected off the white sheet of paper. Turn off the blue light and turn on the green. Adjust the brightness of the green projector so that the photometer indicates the same intensity as was measured with the blue. Turn off the green and turn on the red. Again, adjust the brightness of the red projector so that the photometer indicates the same intensity as was measured with the blue. Now turn on all three projectors — the white paper will appear to be truly white and the other colors will look vibrant and realistic. Having "defined" white empirically in this manner, we can now move on to experiment with the collage.

Pick any swatch of color on the collage, say yellow, and aim the photometer at it. Turn on the blue projector and note the amount of blue light reflected by the yellow paper. Turn off the blue and turn on the green. Adjust the brightness of the green projector so that the photometer indicates the same intensity as was measured with the blue. Turn off the green and turn on the red. Again, adjust the brightness of the red projector so that the photometer indicates the same intensity as was measured with the blue. Now turn on all three projectors. Amazingly enough, the yellow looks quite natural, as do the rest of the color swatches. The spectro-photometer has read equal intensities of reflected red, green, and blue light off the paper and, if queried, would say that the paper is white. After all, that's how we "defined" white. Thus, the spectro-photometer is not capable of categorizing the colors of objects. On the other hand, we can determine without any trouble that the color of the paper is yellow. The eye is our photometer and we are not fooled because it is working in concert with the brain.

One can repeat this experiment for any of the other colors with similar results. It turns out that the yellow, green, and blue swatches work best in that the perceived color looks very much like the color you see when viewing in daylight. Magenta is the worst in the sense that it does not look very much like magenta. It is of course subjective, but more experimentation is in order to explain why.

Setting It Up

The three slide projectors sit on a dedicated cart. A camera tripod, positioned next to the projectors, holds the photometer. The poster sits on an easel situated about 2 meters in front of the projectors.

All the room lights need to be off.

Comments

Although not as sophisticated as Land's original experiment, this re-creation works remarkably well. One drawback is that the Pentax Spotmeter has no output aside from its analog meter, which must be viewed through the eyepiece. It is worth investigating alternatives, or possibly adapting a video camera to the eyepiece so that the audience can view the photometer readings. Better yet would be a photodetector/spectrometer combination enabling one to see the reflection intensities across the entire visible wavelength spectrum. One could then compare and contrast these spectra with what one perceives. For those interested in seeing the original, the Harvard Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments houses many of Land's experimental materials, including equipment and sketches that Land used to develop Retinex theory.

Notes

1 Edwin Land, "The Retinex Theory of Color Vision," Scientific American 236(6), 108-128, (December, 1977).

2 Kodak Ektagraphic III slide projector

3 Kodak Wratten 2 tri-color filters #29 (red), #61 (green), and #47 (blue). These are available from Kodak Cinema & Television (800) 621-3456. The website is motion.kodak.com Spectral transmission graphs are available.

4 Lutron® 600 W rotary dimmers mounted in an electrical box.

5 Selected colors from HUE SET (37 colors) from Coloraid.com. It is a set of calibrated saturated colors (plus white, gray, and black) on paper having a matte finish to minimize specular reflection. Their website has useful information. (Land used these papers.)

6 Pentax Spotmeter V: With a 1 degree angle of view, it is possible to take accurate reflection measurements of specific areas on the poster (an area about the size of a quarter), one wave band at a time. Meter measuring range is 1 - 19 EV.

A meter/filter calibration was performed by measuring the intensity of reflected light off the white matte paper illuminated by the mid-day sun (a source of "white" light). Separate measurements were taken through the red, green, and blue filters. It was found that the reading through the green filter was 2/3 EV higher than the blue, and the reading through the red filter was 2 EV higher than the blue. These "calibration" numbers are used to adjust the measurements in the collage experiment. For example, whatever the level of intensity of blue light reflected off some color is, the green projector will be adjusted so that the reflected light intensity is 2/3 EV higher than the blue reading, and the red projector will be adjusted so that the reflected light intensity is 2 EV higher than the blue reading. One can verify that these "corrections" work properly by applying them to reflections off white paper; the white paper looks pure white when illuminated by the three projectors but does not w/o the corrections.