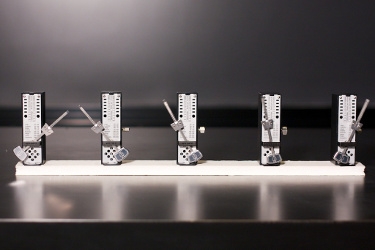

What it shows:

The "tick-tocks" of five metronomes will come into synchronization when weakly coupled together.

|

|

How it works:

The five metronomes sit on a very light FoamCore® board which, in turn, is supported by two aluminum cans on their side. The support is so light that it can react to the side-to-side motion of the metronomes' arms, thus coupling them weakly. Although seeing the arms swing together is impressive, hearing the "tick-tocks" come into sync is marvelous and adds a lot to the demonstration. From random, to syncopated rhythms, to unison.

As an introduction, it's instructive to demonstrate that the five oscillators (metronomes) are not precisely identical; start them together in synchrony on the FoamCore board just sitting on the lecture bench and watch them soon get out of phase with each other, notwithstanding that they are all set to the same number of bpm. Having shown this, starting them randomly and then observing them phase lock (when supported by the cans) is even more impressive.

One can easily change the phase and coupling between the oscillators by simply orienting them at an angle relative to the base board and explore how that affects the system. Additional parameters that can be varied are (1) the average frequency (bpm), (2) the frequency difference between oscillators (add a dot of modeling clay to the pendulum arm for fine tuning), (3) the base mass, and (4) the damping (maybe put a little oil or other viscous fluid in the aluminum can?).

Occasionally anti-phase locking will happen, but we have not explored under what special conditions this happens. It certainly appears at the higher frequencies. Prof Lars English at Dickinson has experimented along these lines and concluded that it depends on the damping of the base motion--more friction induced the transition (private communication). Apparently Christian Huygens was the first to observe the phenomenon of clock sychronization and inaugurated the study of coupled oscillators. His two pendulum clocks phase locked at 180 degrees (anti-phase).

Setting it up:

The metronomes are Wittner TAKTELL SUPER MINI with a frequency range of 40 to 208 bpm (Largo - Prestissimo). The Presto range works well for this particular set-up. At 176 bpm, they rapidly (within a minute or so) get into sync.

Comments:

In a paper entitled "Synchronization of metronomes," Am. J. Phys 70(10), 992-1000, James Pantaleone developed a mathematical model for the metronome system, and discusses how it provides a mechanical realization of the Kuramoto model for synchronization of biological oscillators. Pantaleone provides many excellent references. "Coupled Oscillators and Biological Synchronization," by S. Strogatz and I. Stewart in Scientific American 269(6), 102-109, is a nice biological introduction with more suggested readings. The phenomenon of spontaneous synchronization is found in circadian rhythms, heart & intestinal muscles, insulin-secreting cells in the pancreas, ambling elephants, drummers drumming, menstrual cycles, and fireflies, among others. Thus, in addition to demonstrating the basic physics, this experiment lends itself to modeling diverse phenomena in the life sciences. Our demonstration is a copy of one that Bryan Daniels (Ohio Wesleyan University) made for his student research work: http://go.owu.edu/~physics/StudentResearch/2005/BryanDaniels/index.html which, in turn, appears to be a copy of Pantaleone's model.